Biology of American Eel

American eels are a catadromous fish species. They spawn in the Atlantic Ocean and travel upstream into freshwater to live the majority of their lives (10-30 years). Upon maturing they will migrate back downstream and return to the Atlantic to reproduce and die.

From the English ‘Cata’ (meaning “down”) and Greek ‘dromos’ (“running”), the term describes the downriver migration that they will make near the end of their life cycle. This unique strategy is opposite from an anadromous fish like an American shad that will run upstream to spawn. Collectively we refer to these as a diadromous fish species.

American eels can occupy a variety of freshwater habitats. Eels can be found in all sizes of rivers and streams as well as in lakes and ponds. American eels have even been found as far upstream as Lake Otsego in Cooperstown, NY, the origin of the Susquehanna River.

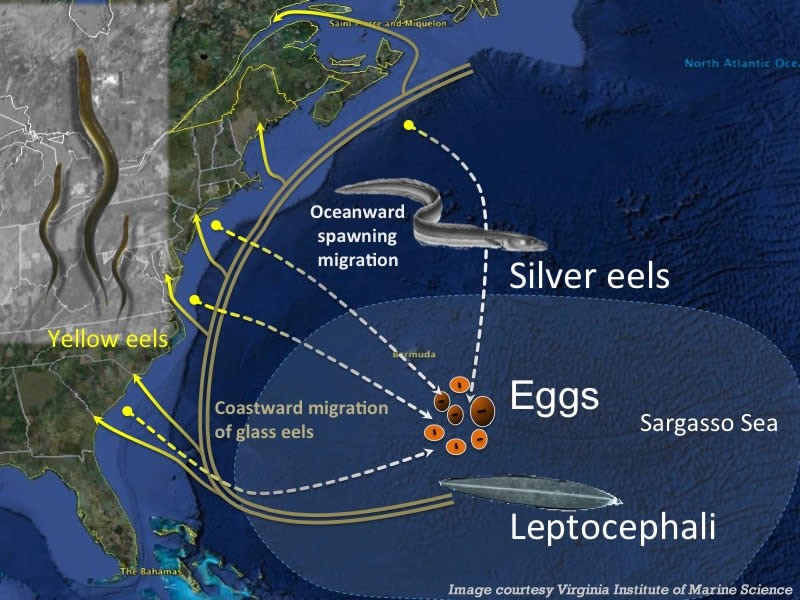

Their journey begins in a vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean known as the Sargasso Sea. This deep, densely vegetated water hosts a free-floating genus of seaweed and many other marine species. It is the only sea without land borders and is defined only by ocean currents. The translucent leaf-like eel larvae, leptocephali, will drift back to the eastern seaboard of North America on these currents. As they approach freshwater, their metamorphosis continues as they develop a more cylindrical body form but retain their clear appearance, earning the life-stage moniker of “glass eel.”

American eels are referred to as ‘elvers’ as they develop pigment and take on a gray color and transition to living in freshwater. Although still only about 4 inches long and weighing less than a nickel, these small fish can swim hundreds of miles against the current to reach their home. Next comes the ‘yellow eel’ phase where they’ll continue to grow and take on a greenish/yellow appearance and are typically 8-20” long. The final stage of the eel’s life prepares itself for its return journey to the ocean to reproduce. The eye enlarges, reproductive organs develop, and its body becomes a dark gray and silver, appropriately known as a ‘silver eel.’ The silver eel has devoted the remainder of its life to a return to the Sargasso Sea where it will breed and start the remarkable process over again.

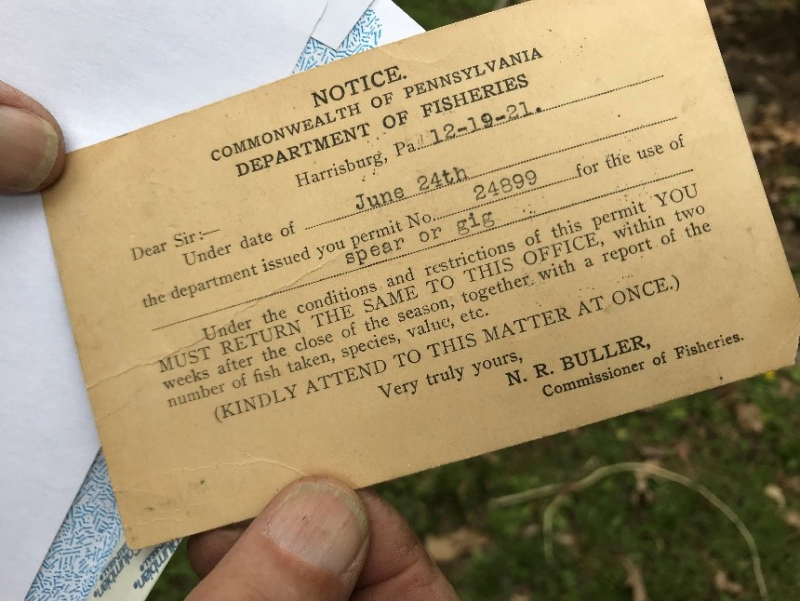

Eels were common table fare for indigenous North American peoples as well as the early European settlers. Great eel weirs were constructed across the river and used to funnel outmigrating silver eels into baskets or traps for harvest. Such weirs were still in use as late as the 1960s. With their migration blocked by the dams, the eel fishery vanished along with a unique piece of the area’s culture. Remnants of old eel weirs can still be seen at low water levels or from above when conditions are right.

Eel life cycle (Photo: VA Institute of Marine Science)

Eel life cycle (Photo: VA Institute of Marine Science)

Eel weir being fished middle 20th century near Sunbury, PA (Photo: Bill Simcox)

Eel weir being fished middle 20th century near Sunbury, PA (Photo: Bill Simcox)

Old eel ‘spear or gig’ permit issued in Pennsylvania (Photo: Van Wagner)

Old eel ‘spear or gig’ permit issued in Pennsylvania (Photo: Van Wagner)

Remnants of a historic eel weir near New Cumberland, PA, October 2020 (Photo: A. Henning)

Remnants of a historic eel weir near New Cumberland, PA, October 2020 (Photo: A. Henning)