PFAS - An Introduction to "Forever Chemicals"

PFAS - An Introduction to "Forever Chemicals"

What are PFAS?

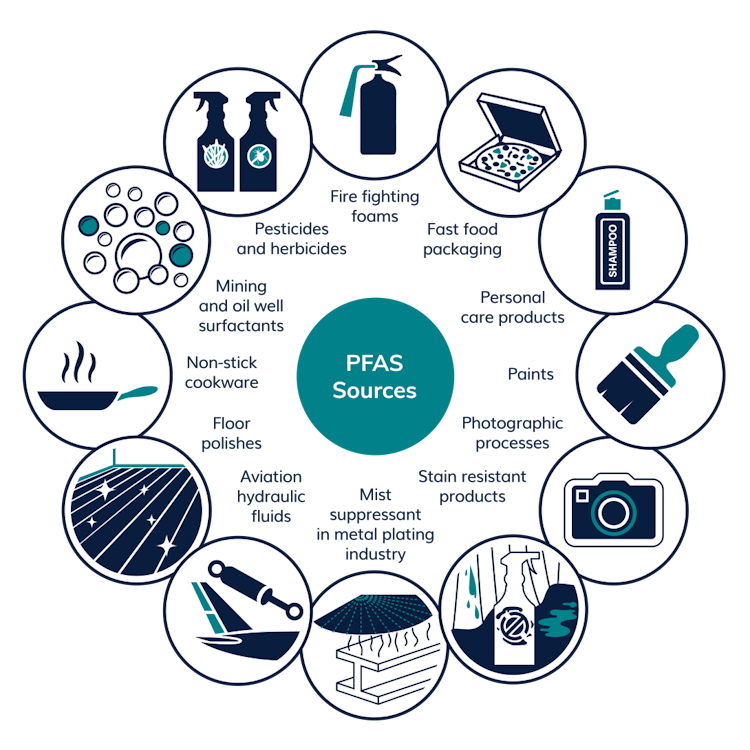

PFAS stand for perfluoroalkyl or polyfluoroalkyl substances — a group of chemicals with properties that allow them to repel water and oil, reduce friction and resist heat. Because PFAS do not break down easily over time, they are often called "forever chemicals."

There are thousands of PFAS chemicals found in consumer, commercial and industrial products. PFOA and PFOS are two types of PFAS that have been most extensively used and studied. PFAS are persistent chemicals that bioaccumulate in living organisms. They are found just about everywhere, even in the blood of most people and animals.

PFAS are found just about everywhere. Pay attention to those exposures you can control as researchers study health effects and discover ways to eliminate PFAS threats.

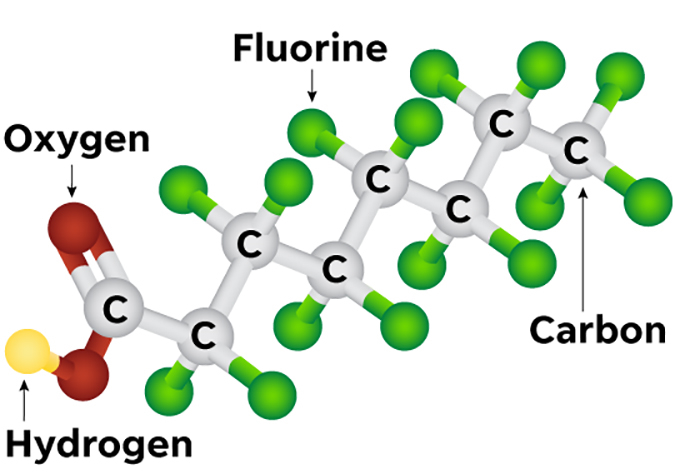

PFAS are made up of a chain of carbon atoms surrounded by fluorine atoms. The carbon-fluorine bond is one of the strongest in nature. This made PFAS super-slippery and great for uses such as grease and water resistance. But it also means natural processes that break down many other compounds — heat, radiation, humidity, dilution — don’t really work on PFAS compounds. Photo: U.S. EPA

In the 1940's, research chemists stumbled upon a new family of chemicals that repelled water and oil. They soon found their way into everyday products—Teflon and Scotchgard were the first commercial products made with these new manmade substances.

Known as PFAS (per and poly-fluoralkl substances), these carbon-and-flourine based chemicals are now considered harmful. Some PFAS have been phased out of production. But they are persistent, long-lived chemicals that are under continued investigation to more fully understand their impacts on the environment and human health.

How Harmful are PFAS?

PFAS are potentially linked to a number of adverse health effects, including high cholesterol, developmental effects including low birth weight, liver toxicity, decreased immune response, thyroid disease, kidney disease, ulcerative colitis and certain cancers, including testicular cancer and kidney cancer

Risks from PFAS exposure may be greatest for those who work where PFAS are manufactured, processed or used, as well as for pregnant and lactating mothers, fetuses and young children.

Some states, including Maryland and New York, have banned PFAS from firefighting foam products.

Are PFAS Regulated?

Although no federal regulation currently exists to set a safe level of PFAS in public drinking water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is working toward finalizing Water Quality Standards for PFAS. Pennsylvania and New York State have set regulatory limits for one or more PFAS.

In 2022, Pennsylvania's new rule established a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for PFOA (14 ppt*) and PFOS (18 ppt). New York's MCL is 10 ppt for both. All 3,117 PA water systems must monitor for these two chemicals and keep track of their running annual average levels.

*ppt = parts per trillion

In local streams, PFA-contaminated foam can be bright white, tends to pile up like shaving cream and can be sticky and lightweight. Naturally occurring foam is usually off-white or brown and has an earthy smell.

What You Can Do

The main routes of human exposure to PFAS are 1) occupational — for people who work with PFAS, and 2) ingestible — via contaminated drinking water, food, or dust and particles. You may not be able to escape PFAS, but you can minimize your exposure by taking the following actions:

- Ask you local water utility if it's tested the water for PFAS. If it has high levels, consider filtering your water for consumption.

- Test your own water but be sure to use a state certified laboratory that uses methods approved by EPA. Homeowners with water wells should have their water sampled if they are concerned about PFAS in their drinking water.

- Buy and use a water filter that is certified to remove PFAS. Both granular activated carbon and reverse osmosis filters can reduce PFAS.

- Replace nonstick pots and pans with stainless steel or iron cookware.

- Do not buy stain-resistant carpets and upholstery.

- Avoid packaging such as bagged microwave popcorn and fast food wrappers and boxes.

- Check for local fish advisories before eating locally source fish or shellfish. Find out which waterways are of concern by contacting your state fish advisory programs.

Evolving Science & Rules

Scientists classify PFAS chemicals as emerging contaminants because the risks they pose to human health and the environment are not completely understood. While scientists explore how to best measure PFAS and their effects, the research has concluded a probable link of PFAS to adverse health impacts in laboratory animals and humans.

Early monitoring of PFAS has focused on locations where potential sources exist such as military bases, landfills, fire training sites, and manufacturing facilities.

U.S. makers of PFAS-related products stopped producing PFOS in 2002 and PFOA in 2013; however, they continue to make a certain type of PFAS that are considered less harmful. More studies are needed. Many PFAS-laden products are still imported into the U.S.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is working toward finalizing Water Quality Standards for PFAS.